- Home

- Ernest Hemingway

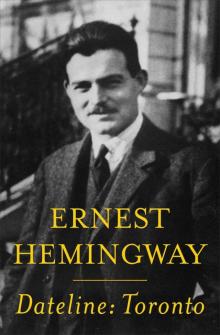

Dateline- Toronto Page 50

Dateline- Toronto Read online

Page 50

McConkey’s 1914 Orgy

The Toronto Star Weekly

December 29, 1923

New Year’s Eve is gone.

No one knows just where it is gone.

But the general opinion seems to be that it has gone over the border in bottles, barrels and cases.

New Year’s Eve dies harder in the States.

Two nights from tonight the time-honored custom of drinking the old year out and watching the new year come in out of a bottle will still be carried on. New Year’s Eve is still celebrated as one great national orgy on the other side of the line.

The writer has attended orgies in all parts of the world. Always they have been dull.

The dancing dervishes of Stamboul are amiable old men who jiggle around as long as the money drops.

The wild dancing of gypsies in the cave in the hill above the Alhambra in Granada is a dull peseta-catching tourist trap.

The average Parisian orgy is a certain soporific.

But a New Year’s Eve in any big city in the States is something else again.

Where else will you see a beautiful young lady dive into a hotel fountain out of pure joy of living?

Where else, if the beautiful young lady took this dive, would she be applauded by the police?

Where else would you see another young lady and her escort fishing in another hotel fountain for goldfish, using their slippers as scoops while the police hold back the crowd to see that there is fair play, and a procession of young men run about the crystal room with their hands on one another’s shoulders, shouting that they were the wild Princetonian shoehorns and that tonight was tonight?

New Year’s Eve as an orgy in Toronto met its death at the hands of Colonel [George Taylor] Denison in February of 1914.

The exact words of the colonel which placed the lid on New Year’s Eve-ing on the American plan in Toronto were uttered in the police court.

“There is plenty of evidence to support the charge,” the colonel summed up. “I think the whole thing was a disreputable affair. As far as I can gather from the evidence, it was just a drunken revel, called an orgy. It was certainly not a respectable thing for thirty or forty women to stagger out of the place and for two or three to have been carried out. We have got the evidence of people who did not want to give evidence. We have got evidence that there was not only noise, but drunkenness, and men kissing their wives and other people’s wives. It was just a revel that should not have been allowed in any respectable house. You could not call it an orderly house independent of the offense of selling liquor. The license will be suspended for sixty days.”

In these words the colonel put the final touch on the New Year’s Eve party in Toronto. That made a terrific stir in numberless families.

It is all legendary now. There are many different versions of what happened at McConkey’s “Tavern” that night and morning. The tale has assumed Homeric proportions with the lapse of the years.

In those days McConkey’s had a lunchroom on the ground floor at King Street where the Bank of Nova Scotia stands now. The lunchroom ran through to Melinda Street and was an eating place famous throughout Canada. It was a daily part of the lives of many Toronto men to drop into McConkey’s for a sandwich and a glass of something or other.

Upstairs were six or seven bedrooms, and on the third floor a ballroom. It was in the ballroom that the party occurred.

Reservations were made for 250 guests. They were to see the old year out and the new year in. Champagne and wine were to lubricate the passage of the discarded year. There was no necessity to pay for the wine. It could all be charged and the bill sent the following week.

A dinner was served sometime early in the evening. This was an established fact. Of the people who testified, a number remembered the dinner.

Just what happened at the party will never be fully established. It is not safe yet to go into the matter. The amazing thing which came out in the police court was that no one had drunk more than three or at most four glasses of champagne. Witness after witness testified to this fact. No one had seen anyone else drunk either.

It seemed there was some doubt as to what constituted being drunk.

One witness said that he had seen no drunkenness and nobody under the influence of liquor.

“When is a man drunk?” was the question.

“When he is incapable of standing, walking or talking,” was the answer.

It seemed to be the general definition.

At any rate Colonel Denison accepted the testimony of the constable who watched McConkey’s disgorge revelers at various hours during the morning.

Policeman John Boyd was the second witness called. He said he came on duty at eleven o’clock, at which hour a good many people, seemingly theater patrons, were entering McConkey’s.

“Between twelve and three o’clock I saw between forty and fifty intoxicated women come out of the restaurant. Two women were carried out and many were led.”

“Did you ever see a woman escorted?” Mr. H. M. Ludwig, K.C., who appeared for Mr. McConkey, asked the constable.

“Yes,” answered Boyd, “but not staggering. There was a great deal of noise, women laughing. Stragglers were coming out of the place at 4 a.m.”

“Weren’t they waiting for their motorcars?” asked Mr. Ludwig.

“They may have been,” answered the constable. “There were a great number of taxicabs lined up.”

Walter Richards, then McConkey’s headwaiter, said he saw no one drunk or even under the influence of liquor, no women acting queerly and heard only a very little noise.

Crown Attorney Corley suggested that Richards was an admirably deaf and dumb waiter.

One of the guests said, “I saw no one drunk but many exhilarated. I left very early after having a fight. On a dance floor a man bumped into a lady with whom I was dancing and I objected. He said he would see me downstairs. I went down with him and, after arguing with him, we had a mild fight.”

Even the fights were mild that night, according to the witnesses.

“I received a crack on the mouth,” concluded the witness.

The other participant in the mild fight said he had heard a good deal of noise, but that was just at midnight when the company sang “Auld Lang Syne,” rattled the windows and blew horns.

“There was a little spasmodic blowing of horns after that,” said he.

In answer to a question of Colonel Denison’s as to when a man is drunk, the witness said, “When he can’t get on a streetcar.”

Still another witness stayed until 1:30. He saw no fighting nor anybody carried out.

“Did you see any kissing?”

“No.”

“Any fighting?”

“No.”

“Anybody under the influence of liquor?”

“Not while I was there.”

“Was there any noise?”

“Not much. Just a good joyful evening.”

One witness, more frank than the others, saw people slightly under the influence of liquor.

“Did you see anyone staggering?”

“Yes.”

“Where?”

“A man was trying to get in.”

“That was not Mr. McConkey’s fault,” Mr. Corley said.

In spite of all that testimony, the colonel did not like the party. He did not like it at all. He liked it so little that there has never been another New Year’s Eve of the sort since in Toronto.

Toronto still has a modified New Year’s revel. Tables are still engaged at downtown hotels and it is said that lawless people still bring certain quantities of forbidden beverage with them to be consumed at their own tables.

The ghost of McConkey’s 1914 party still approaches those tables. But it starts away in alarm. It is a very timid ghost. It is afraid of Colonel Denison and his successors on the bench.

Our Modern Amateur Impostors

The Toronto Star Weekly

December 29, 1923

Last Septembe

r in Montreal I chanced to go to a prizefight. The fights were not much. None of the fighters got much of a hand. But there was one popular figure.

“Gentlemen and ladies, allow me to introduce to you Kid Lavigne, former lightweight champion of the world,” the announcer bellowed. The Kid, short, middle-aged, looking like a pocket edition of Gentleman Jim Corbett under the lights, bowed at ease, his hands on the ropes. “One of the greatest fighters of all time,” finished the foghorn voice.

Crash! came the applause.

“Kid Lavigne, ladies and gentlemen, has consented to referee the next bout,” megaphoned the announcer.

More applause.

I felt that even if the bouts were dull, I had at least seen Kid Lavigne. It is something to see a champion of the world. So he was stored away in memory, a short, competent-looking little man, the lights above the ring shining on his smoothly brushed hair.

A few weeks ago came the announcement in the paper that the former lightweight champion of the world, Kid Lavigne, had been granted a marriage license in Detroit. Mr. Lavigne, the dispatch said, was employed in the Ford plant.

That seemed funny.

Last week a wire from Montreal brought the information that a referee’s license which had been issued to a man posing as Kid Lavigne had been canceled upon the discovery that the former lightweight champion was in reality living in Detroit and working in the Ford plant. The man claiming to be Kid Lavigne had photographs, letters and clippings to prove he was the real Kid, but his story had been discredited by a sportsman who had seen the real Saginaw Kid in action in the old days.

Why do they do it?

What is the impulse in a man that makes him pass himself off as someone else, often to make himself believe he is someone else, facing in the end almost sure detection?

This article does not deal with the bad-check passers, the fakers, the sordid swindlers, but with the amateur impostor, that strange type of man who has some queer kink in his imagination that makes him give himself the personality and adventures of some other person. This kink may be the same that in another man would make a Joseph Conrad or a great painter.

You encounter these amateur impostors often enough. One summer we were playing baseball in northern Michigan. A slight-built young fellow appeared one day in front of the grandstand out at the Petoskey fairgrounds and started to warm up with the regular pitchers. He was Dixie Davis of the St. Louis Browns, he told the gang.

Naturally, he obtained plenty of attention. He threw a nice curveball and seemed to have plenty of stuff. He wasn’t cutting loose, he explained. He was up in Petoskey because he had disputed one of Umpire Billy Evans’ decisions, and been suspended. It was too hot in St. Louis and he was taking a vacation during his suspension.

On the following Sunday, we played Traverse City at our home grounds in Charlevoix. I was assigned to persuade Dixie Davis to pitch for us. It was not a very difficult task. He would be glad of the workout. Sure. He’d be there all right. It would help him keep in shape.

All we had to do was send a motorcar to drive him over and get him a uniform.

We sent the car. But at the hotel they declared he had already left to go to Charlevoix.

“He’s pitching there this afternoon,” the hotel clerk said. “I wish I could have got off for the game.”

Dixie didn’t show up. Two days later we read in the papers that Dixie Davis had shut out the New York Yankees that very same Sunday in St. Louis.

It may seem a long jump from an imitation Dixie Davis back to George Psalmanazar. But the line runs straight back to 1704 in the city of London. On its way back it takes in Jacques Richtor, of the Great North. Jacques is too recent in memory to need explanation.

George with the funny last name arrived in London, a dark, swarthy young man, obviously a foreigner. He could speak no word of English, but learned quickly.

As soon as he could speak any English, he started enlisting the aid of England for his native land of Formosa, from which he had come by many perilous adventures. He wanted missionaries there. The Bishop of London was one of his most ardent supporters.

He published a book which was received with great acclaim. It was called A Historical and Geographical Description of Formosa. It recounted the habits, language, dress and character of the inhabitants of that distant land. It also described the Formosan scenery, buildings, wars, politics, poets and statesmen. There was no doubt about it. It was an important work.

Psalmanazar filled his books with drawings of the Formosan royal family and illustrations of its buildings. He constructed a language and a grammar and taught English students to understand them. He appeared before scientists and gave lectures on the Formosan language at Oxford.

This wonderful book was dedicated to the Bishop of London. Formosa was as much the topic of conversation then as King Tut’s tomb was last year.

When the crash finally came, Psalmanazar admitted he was a native of Languedoc, France. He had come to England as an immigrant. He was exposed by a few hardy doubters who had mistrusted him from the start.

Dr. [Frederick A.] Cook was a piker beside Psalmanazar, although many people feel that the doctor’s mountain-climbing adventures in the West, including his ascent of Mount McKinley, were much more finished and delicate bits of work than the North Pole business.

Captain J. A. Lawson was a splendid forerunner to Cook and Richtor. The captain wrote Wanderings in New Guinea in 1875. There was nothing coarse about this work. Deftly and one-by-one, the navigator got rid of his traveling companions. You hardly notice they have gone until you reach the last page and there is no one to return with the adventurous captain.

Tooloo the Lascar goes mad and shoots himself with Captain Lawson’s rifle by putting the muzzle in his mouth and pulling the trigger with his toe. Hostile natives slay Joe, the splendid young Australian. Danong, the courageous Papuan, dies by the same hands. Aboo, another guide, disappears a little later. Billy, the Australian aborigine, the last survivor, deserts the captain at Singapore.

There is only the courageous captain. And what a welcome he received. He discovered it. He had been to the top of the world on Mount Hercules, a smile higher than Mount Everest. Everest, you remember, was unscalable to a British exploring party last year. They could not get sufficient oxygen.

Lawson, as he neared the summit of Mount Hercules, also encountered difficulty. “The cold now became excessive,” he wrote. “My hands were so numb I could not feel whether I had fingers or not. The water in our bottle was a mass of ice. We had very little extra clothes with the exception of our blankets. Aboo became quite lethargic, and several times sat down and fell asleep.”

Still they climbed.

Poor Lawson’s downfall came when a certain Captain Moresby, a British naval officer, who at the time of the publication of the captain’s book happened to be out in his old stamping ground. The gallant captain gave certain latitudes and longitudes in his book. Captain Moresby had charted those waters and was able to prove that the explorer’s principal village was situated in the middle of Torres Strait.

No one ever learned whether Captain Lawson had ever been in New Guinea or not. He wouldn’t tell.

Two years ago Louis de Rougemont died in a London poorhouse. To the poorhouse authorities he was plain Louis Redmond. But Louis was one of the greatest of them all.

The year the Boer War started the Wide World Magazine announced with pride the publication in serial form of the “Amazing Adventures of Louis de Rougemont,” as recounted by himself. Louis had just arrived in London on a vessel straight from New Zealand. He talked with conviction. His story still makes good reading.

Louis was no piker. For thirty years he had wandered among the cannibals. It started in the West Indies in a pearling expedition. There was action from the start. After a thrilling battle with an octopus, who had sucked down a native diver, Louis is left alone on board the pearler one day and blown out to sea.

He is cast away on a sandy island and makes hi

mself a sort of super Emperor Jones. He acquires the wonderful Wamba. There was never anyone so wonderful as that dusky spouse.

She fights with him and nurses him. Louis was a fighter, too. His wonderful charge is an epic. He even wields a hefty spear as well as a long bow.

Toward the last of the narrative two girls from the homeland are washed up on the island. Like Louis they are castaways. They like Louis, too.

Whether Wamba became jealous is not stated but the good old sea takes the girls for its own. It is a sad loss. But Louis has Wamba to console him.

Then comes the cry of “A Sail! A Sail!” And the long homeward voyage. Thus it was that the great story of thirty years among the cannibals came to be told.

It sounds fishy? But de Rougemont was invited to tell the story to a British scientific society.

The Daily Chronicle, which exposed Dr. Cook, burst Louis de Rougemont’s bubble. His thirty years with the cannibals had been spent with Swiss bankers. His tropical island had been the dull streets of London. Louis’ thirty years had been spent in the routine of a London banking house.

Still, at the age of 67 he made a comeback and married a brilliant young woman who tells how he entertained her for some time with his wonderful imagination.

There is one case in the annals of the great impostors where the impostor was honestly deceived.

While the science of geology was still in the hands of its earliest pioneers, Professor Beringer lectured at the University of Würzburg. In his old class were a number of bright young men who knew the haunts of the genial old man in his hunt for fossils that would develop his theories about the origins of life. These students paid nocturnal visits to the professor’s favorite hunting grounds.

Shortly after, the professor’s hammer and bright eye discovered evidence of a totally new kind of extinct life. He found fossil frogs, snakes and insects galore.

The students were inspired by his enthusiasm.

There was almost nothing the professor couldn’t find. One day he found a cast of a spider in its web and not one strand disturbed although it had come through the grinding of hundreds of thousands of years. Then came another fossil of a spider in the act of catching a fly.

The Old Man and the Sea

The Old Man and the Sea Green Hills of Africa

Green Hills of Africa The Sun Also Rises

The Sun Also Rises Death in the Afternoon

Death in the Afternoon In Our Time

In Our Time For Whom the Bell Tolls

For Whom the Bell Tolls A Farewell to Arms

A Farewell to Arms A Moveable Feast

A Moveable Feast The Complete Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway

The Complete Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway Big Two-Hearted River

Big Two-Hearted River Winner Take Nothing

Winner Take Nothing Islands in the Stream

Islands in the Stream To Have and Have Not

To Have and Have Not The Snows of Kilimanjaro and Other Stories

The Snows of Kilimanjaro and Other Stories Across the River and Into the Trees

Across the River and Into the Trees By-Line Ernest Hemingway

By-Line Ernest Hemingway True at First Light

True at First Light Men Without Women

Men Without Women The Nick Adams Stories

The Nick Adams Stories Dateline- Toronto

Dateline- Toronto The Torrents of Spring

The Torrents of Spring Short Stories

Short Stories